Against the backdrop of the rolling hills and serene environment of the Ikogosi Warm Springs resort in Ekiti, Corporate Accountability and Public Participation Africa (CAPPA) held a first-of-its-kind youth boot camp on food justice from August 24 to 29.

Supported by the Global Health Advocacy Incubator, the five-day gathering brought together 52 carefully selected participants from Nigeria’s six geopolitical zones to deliberate on strategies for advancing healthy food policies and curbing the rising burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in the country.

In his welcome address, CAPPA’s Executive Director Akinbode Oluwafemi stated that Nigeria’s health profile is changing with the increasing burden of NCDs. Nearly one in three deaths in the country is now linked to hypertension, diabetes, strokes, and cancers, according to statistics. These illnesses are largely tied to the increasing consumption of ultra processed foods high in salt, sugar, and fat. He warned that multinational corporations have turned Nigeria into a dumping ground for cheap calorie-dense products that fuel long-term health problems. To address this, he called for stronger implementation and enforcement of healthy food policies, including the sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) tax, mandatory salt reduction targets, and clear front-of-pack warning labels.

If Oluwafemi exposed the scale of the public health crisis, Professor Adelaja Odutola Odukoya, Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Lagos, unpacked the politics of the junk food industry. His opening lecture, “Movement Building, Youth Activism and the Quest for Healthy Food Policies,” situated the struggle for food justice within the wider history of power and resistance. Societal imperfections, he reminded participants, do not yield to persuasion but to organised struggle. Quoting Frederick Douglass’s timeless words that “power concedes nothing without a demand,” he argued that the struggle for food justice is not a charitable appeal but a confrontation with power. Meaningful change, he insisted, requires collective action and a belief in the possibility of transformation sustained over time.

Professor Adelaja defined food justice as both a right and a movement. It is the right of communities to access nutritious and culturally relevant food, and it is inseparable from the principles of food sovereignty and sustainable agriculture. Yet, he cautioned, this right is constantly under attack from a food industry driven by profit. For that reason, young advocates must take ownership of the struggle and recognise that the state remains central to shaping food policy. To reclaim power over the food system, citizens must demand a say in what is produced, how it is cultivated, and how it is distributed and consumed. His lecture further offered a roadmap for effective policy advocacy. A successful campaign and movement, he said, requires strategy, tactics, and a clear demand. Narratives matter because they frame the struggle, unify actors, and allow advocates to speak truth to power in ways that cannot be easily ignored.

Picking up from Professor Adelaja’s framing of food justice as a political movement, Abayomi Sarumi, Associate Director of CAPPA’s Food Justice Programme, shifted the focus to the mechanics of how corporate power operates in practice. His session which helped participants understand CAPPA’s Healthy Food Policy Campaigns, showed how the fight for justice is as much about exposing harmful corporate actions as it is about advancing public health. He explained that global food and beverage corporations rely on what he termed the five commercial determinants of health: lobbying to influence policymakers, aggressive advertising to capture consumers, political capture to weaken state oversight, litigation threats to intimidate regulators, and philanthro-washing to mask harmful practices under the cover of charity. Sarumi’s analysis revealed that these tactics are actively shaping Nigeria’s food environment. He encouraged participants to note that food justice is not only about nutrition but also about challenging the calculated engineering of public appetite by powerful economic actors.

Health expert Dr. Joseph Ekiyor, in his presentation “The Burden of NCDs in Nigeria and the Imperative for Urgent Interventions,” explained how unhealthy diets are driving hypertension, kidney failure, strokes, and premature deaths. He highlighted everyday foods—shawarma, noodles, bread, pizza, and bouillon cubes—marketed as convenient but carrying serious health risks. He stressed that each preventable illness reduces productivity, depletes family income, and adds pressure to Nigeria’s already fragile healthcare system.

DAY TWO

The day opened with a session on the Economics of the SSB Tax, delivered by economic analyst Austin Iraoya, who drew on global case studies from Mexico, South Africa, and the UK to show how well-designed pro-health taxes can reduce consumption and save lives. The obstacle, he said, was not public indifference but industry interference, often carried out through lobbying proxies. The youth, he argued, must learn to reframe the SSB tax as a life-saving measure rather than just a revenue stream. He added that advocacy for raising the tax should be anchored on global best practices, noting that the World Health Organization recommends tax rates of between 20 and 50 percent of retail prices to achieve meaningful public health impact.

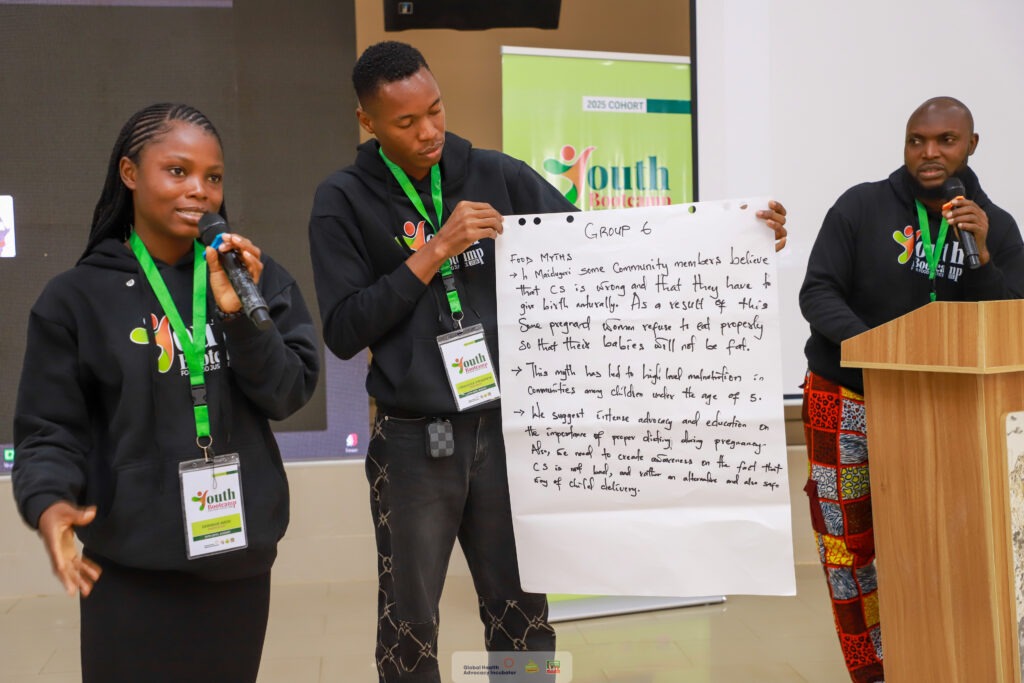

The political dimension of the struggle was highlighted by CAPPA’s Assistant Executive Director, Zikora Ibeh, who led a session on Activating Policy Through Public Health Activism. She described public policy as a product of the state and activism as the catalyst for change, emphasising the vital connection between the two. She noted that influencing policy requires activism that is deliberate and well-structured. Outlining the core elements of a successful campaign, she stressed the importance of clear goals, specific objectives, defined expectations, realistic timelines, and strong mechanisms for monitoring and evaluation. To close the session, participants were divided into teams and asked to identify a pressing public health issue and design a strategy to tackle it. The exercise shifted theory into practice, turning abstract ideas into concrete, actionable plans.

From there, the sessions broadened into law and storytelling. Barrister Shade Oyelade-Osi, CAPPA’s legal and policy officer, walked the camp through the complex lattice of Nigeria’s Food Policies and Laws—the constitutional guarantees, the regulatory mandates of National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control and the Standards Organisation of Nigeria, the oversight of the Federal Competition and Consumer Protection Commission, and the pending National Food Safety Bill before the country’s legislative house. She warned that while Nigeria’s legal frameworks were strong on paper, weak enforcement and regulatory capture continue to undermine them in reality.

Photographer and digital storyteller Wale Obayanju reminded participants that numbers alone rarely move people, but stories do. His session, “Tell That Story, Drive That Policy,” flagged the need for narratives grounded in dignity and authenticity. Food, he argued, is a universal language, and the way its story is told can either expose injustice or reinforce it.

In a session on security, Tommie Ogundiran, Lead Consultant at Infoscert, and Idris Abiodun, CAPPA’s IT Manager, led a practical discussion on safety. Titled “Securing the Movement,” the presentation reminded participants that advocacy sometimes carries risks in both digital and physical spaces. Encryption, two-factor authentication, and cautious online practices were shown to be just as important as situational awareness and physical self-protection. Through simulations of compromised safety, participants came to see that without security, no campaign can endure. Safety is not an afterthought but the foundation of effective advocacy. When social justice campaigners are left vulnerable, movements lose momentum and impact. For this reason, integrating safety measures into planning and execution is essential to ensure that campaigns remain active, resilient, and effective over time.

DAY THREE

By the third day, the camp had shifted into counter-offensive. Sarumi returned to lead a session on Industry Monitoring, exposing the “deny, dilute, and delay” strategies of Big Food. Afterwards, participants worked in groups to design campaigns that could challenge and expose deceptive industry narratives.

The global stakes were outlined by Joy Amafah-Isaac, GHAI’s in-country coordinator, in her presentation Global Outlook and Perspectives on the SSB Tax. She showed how corporations rely on the same playbook worldwide—pushing for weak taxes, threatening lawsuits, funding counter-science, and portraying pro-health measures as “anti-poor.” Yet she noted that the tide is shifting: 107 countries have now adopted SSB taxes, and early evidence from Mexico and the UK shows significant declines in sugar consumption.

CAPPA’s Communications Officer, Robert Egbe, and videographer, Simeon Hella, guided participants deeper into the craft of media advocacy. Egbe shed light on the architecture of effective campaigns—who delivers the message, how it is framed, where it is placed, and the impact it is designed to achieve. Hella complemented this with a hands-on approach, urging participants to embrace creativity and make use of simple tools—smartphones and free apps—to produce compelling advocacy content.

The skills shared during the day carried into the evening, when a creative studio at the boot camp came alive with music and skits. Reflex Soundz, a music producer, worked with participants to turn their ideas into soundtracks and spoken-word pieces built around healthy food policies.

DAY FOUR

On the fourth day, attention turned to cardiovascular health (CVH). Bukola Olukemi-Odele, CAPPA’s CVH Programme Officer, explained how excessive salt consumption is driving the rise of strokes and heart disease in Nigeria. She noted that front-of-pack labels can help consumers track their sodium intake in real time, while broader interventions such as NAFDAC’s National Sodium Reduction Guidelines provide a pathway for reducing salt intake at the population level.

In the session that followed, human rights campaigner Hassan Soweto reminded participants that activism is not only about confrontation but also about Resilience and Holding the Line Without Burning Out. He warned that burnout is the silent killer of movements, describing its symptoms as loss of passion, feelings of paranoia, and recurring illness. He urged participants to treat both self-care and collective care as political obligations, stressing that the struggle must be understood as a marathon rather than a sprint.

That afternoon, the camp staged a solidarity march through the resort with banners calling for healthy food policies. A Nigerian food exhibition led by Healthy Food Curators, Olapeju Ibekwe and Damlex Restaurant, taught participants how to make natural spices from scratch and served local dishes such as amala, tuwo shinkafa, ofada rice, and vegetable soups prepared without monosodium glutamate or processed seasonings. In the process, participants rediscovered that traditional cooking methods, once displaced by processed shortcuts, offer both health and pleasure. Reclaiming food culture in this way resists corporate control of diets and shows that nutritious, affordable meals already exist within local traditions.

A spirited debate on whether sugary drinks should be highly taxed showcased the analytical skills of the youth. The winning team drew on international evidence, citing Mexico’s 37 percent drop in consumption after the introduction of the SSB tax and the UK’s removal of 45 million kilograms of sugar from soft drinks through product reformulation as strong grounds for increasing the tax. Their proposals went further, recommending a shift from fixed levies to percentage-based taxation, transparent allocation of revenue to health funds, and nationwide awareness campaigns to counter industry misinformation.

Towards the close of the camp, CAPPA’s Programme Officer, Opeyemi Ibitoye, linked these discussions to the organisation’s broader national campaign. She highlighted the work of the 130-member SSB Tax Coalition and the Healthy Food Policy Youth Vanguard, alongside innovative outreach strategies that ranged from “sip and paint” events to digital challenges. She stressed that effective policy advocacy depends on building community power capable of influencing governance processes.

By August 29, when certificates of participation were presented and a bonfire lit to close the camp, the fifty-two participants were no longer passive learners. They had debated law and economics, marched with banners, cooked traditional meals, crafted skits, written tweet storms, and encountered the hard truth of what it means to challenge a global industry that profits from ill health. In their closing reflections, they thanked CAPPA for creating such an enlightening platform and for the lessons gained, pledging to put their new knowledge and skills to work in driving greater change.